Senecan tragedy

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2008) |

Senecan tragedy refers to a set of ten ancient Roman tragedies, eight of which were probably written by the Stoic philosopher and politician Lucius Annaeus Seneca.

Senecan Tragedies[edit]

The group comprises:

- Hercules Furens

- Medea

- Troades

- Phaedra

- Agamemnon

- Oedipus

- Phoenissae

- Thyestes

- Hercules Oetaeus

- Octavia

Hercules Oetaeus is generally considered not to have been written by Seneca, and Octavia is certainly not.[1] Many of the Senecan tragedies employ the same Greek myths as tragedies by Sophocles, Aeschylus, and Euripides; but scholars tend not to view Seneca's works as direct adaptations of those Attic works, as Seneca's approach differs, and he employs themes familiar from his philosophical writings.[2] It is possible that the style was more directly influenced by Augustan literature.[3] Moreover, Seneca's tragedies were probably written to be recited at elite gatherings, due to their extensive narrative accounts of action, dwelling on reports of horrible deeds, and employing long reflective soliloquies.

Usually, the Senecan tragedy focuses heavily on supernatural elements. The gods rarely appear, but ghosts and witches abound.

Reception[edit]

In the mid-16th century, Italian humanists rediscovered these works, making them models for the revival of tragedy on the Renaissance stage. The two great, but very different, dramatic traditions of the age—French neoclassical tragedy and Elizabethan tragedy—both drew inspiration from Seneca.

The plays also gained prominence in English-speaking countries, as Senecan drama was some of the first classical work to be translated into English during this period.[4] The first complete translated collection of all of the plays attributed to Seneca at the time was Seneca: His Tenne Tragedies, compiled and edited by English poet and translator Thomas Newton.[5] The plays were translated by Jasper Heywood, Alexander Nevyle, Thomas Nuce, John Studley, and Newton himself.[4]

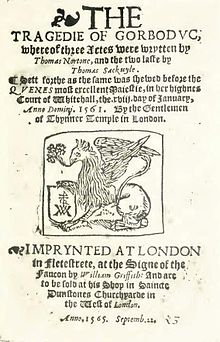

The Elizabethan dramatists found Seneca's themes of bloodthirsty revenge more congenial to English taste than they did his form. The first English tragedy, Gorboduc (1561), by Thomas Sackville and Thomas Norton, is a chain of slaughter and revenge written in direct imitation of Seneca. (As it happens, Gorboduc does follow the form as well as the subject matter of Senecan tragedy: but only a very few other English plays—e.g. The Misfortunes of Arthur—followed its lead in this.) Senecan influence is also evident in Thomas Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy, and in Shakespeare's Titus Andronicus and Hamlet. All three share a revenge theme, a corpse-strewn climax, and The Spanish Tragedy and Hamlet also have ghosts among the cast; all of these elements can be traced back to the Senecan model.

French neoclassical dramatic tradition, which reached its highest expression in the 17th-century tragedies of Pierre Corneille and Jean Racine, drew on Seneca for form and grandeur of style. These neoclassicists adopted Seneca's innovation of the confidant (usually a servant), his substitution of speech for action, and his moral hairsplitting.

The 1800s saw a period of general disparagement of Senecan drama, as criticism surrounding the violence and supposed monotony of the plays flourished.[6] This would last until the 20th century, when interest surrounding the scholarship and performance of Seneca's plays had two prominent periods of revival. These resurgences occurred in the 1920s and the 1960s, with the latter continuing to the modern day.[6]

The renewed interest in Seneca's works in the 1920s was largely concerned with writing and analysis of the plays, rather than their performances. Some possible reasons for this interest were World War I, the violence of which could be related to the violence in the plays, and the popularization of psychoanalysis, which gave a new lens through which critics could analyze the characters.[6] T.S. Eliot gave an influential address in 1927 connecting Senecan drama with the works of Shakspeare and refuting past criticisms.[7]

The revival of the 1960s was characterized by interest in the staging and production of Seneca's plays, which may have been sparked by the bimillennial anniversary of his death in 1965.[8] An especially prominent restaging was English poet Ted Hughes' 1968 production of Oedipus. Hughes wished to highlight what he saw as the primitive savageness of the play, which he conveyed through a lack of punctuation in the script.[6] The production was directed by renowned English director Peter Brook, who drew heavily from Antonin Artaud's Theater of Cruelty to emphasize the violence and bloodshed of the play.[9] Productions of Seneca's work continued to appear into the 1980s. Stagings of Troades, Medea, and Phaedra, for instance, were published, performed, and directed by translator Frederick Ahl. These stagings were noticeably less violent and closer in tone to the original plays than the stagings of Hughes.[6]

Senecan drama continues to draw attention into the modern day. Of particular note is Theyestes, which has been translated in 1994 by British playwright Caryl Churchill and in 2010 by Australian director and actor Simon Stone.[9]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature". Oxford University Press.

- ^ Buckley, Emma; Dinter, Martin, eds. (2013). A Companion to the Neronian Age. Blackwell Publishing.

- ^ Tarrant, R. J. (1978). "Senecan Drama and Its Antecedents". Harvard Studies in Classical Philology. 82: 213–263. doi:10.2307/311033. JSTOR 311033.

- ^ a b van Zyl Smit, Betine (2012). "Jasper Heywood's Translations of Senecan Tragedy". Acta Classica. 55: 99–117. ISSN 0065-1141.

- ^ Seneca (1966-01-01). Seneca: His Tenne Tragedies Translated into English. Edited by Thomas Newton, introduction by T. S. Eliot. Indiana University Press.

- ^ a b c d e Harrison, Stephen (2009-05-01). "Some Modern Versions of Senecan Drama". 1 (1): 148–170. doi:10.1515/tcs.2009.008. ISSN 1866-7481.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Eliot, Thomas Stearns (1927). Shakespeare and the Stoicism of Seneca: (An Address Read Before the Shakespeare Association 18th March, 1927). Shakespeare Association.

- ^ Ziolkowski, Theodore (2004). "Seneca: A New German Icon?". International Journal of the Classical Tradition. 11 (1): 47–77. ISSN 1073-0508.

- ^ a b "Reception of Senecan Tragedy | APGRD". www.apgrd.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2024-05-14.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 494–495.

- Hicks, Robert Drew (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 637.